By Aaron Person and Joanie Holst

This article originally appeared in the Wayzata Historical Society newsletter The Telegraph. It has been republished here with permission from the Wayzata Historical Society.

Like many other spots on Lake Minnetonka, the peninsula we know today as Bracketts Point has gone by many different names in its long history. Also known as Promontory Point, Starvation Point, Printers Point, and Orono Point, to name just a few, it was eventually named after its most well-known settler George A. Brackett and his wife Annie Hoit Brackett.

George and Annie Brackett first visited Lake Minnetonka on August 18, 1858 for a picnic and day of fishing and camping with friends. It wasn’t until 1880 that the Bracketts returned to Lake Minnetonka to purchase the peninsula between Browns Bay and Smiths Bay. Mr. and Mrs. Brackett gave it the name Orono Point and built a modest cottage at the site. The name Orono was important to George Brackett, as he had left his home of Orono, Maine to come to Minnesota in 1857. It wasn’t until 1930 that it was renamed Bracketts Point in his honor.

George Brackett had already garnered a long list of accomplishments prior to his 1880 purchase. These included:

- Meat supplier for the First Minnesota Volunteer Regiment

- Successful milling career

- Founding member of the Minneapolis City Council

- Mayor of Minneapolis (elected 1871)

- Chief Engineer of the Minneapolis Volunteer Fire Department

After establishing himself at Lake Minnetonka, Brackett became an active member of the early sailing community and was named the first commodore of the Minnetonka Yacht Club in 1882.

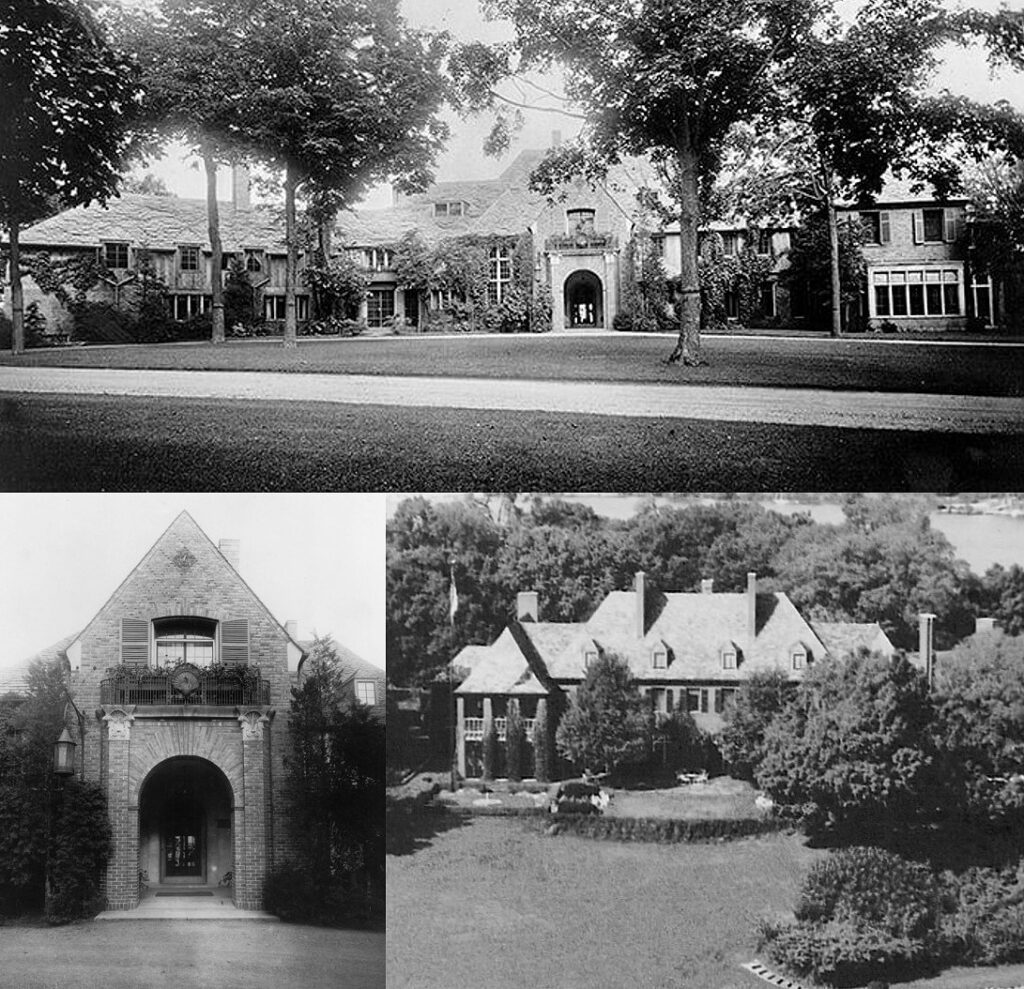

Beginning in 1890, the property along the Browns Bay side of Bracketts Point was owned by William Hood Dunwoody. Dunwoody commissioned Minneapolis architect William Channing Whitney to design a summer cottage for his family on the point. Designed in the Colonial Revival style, the cottage received at least one addition to its south side by 1905. The Dunwoodys named the home Pennhurst.

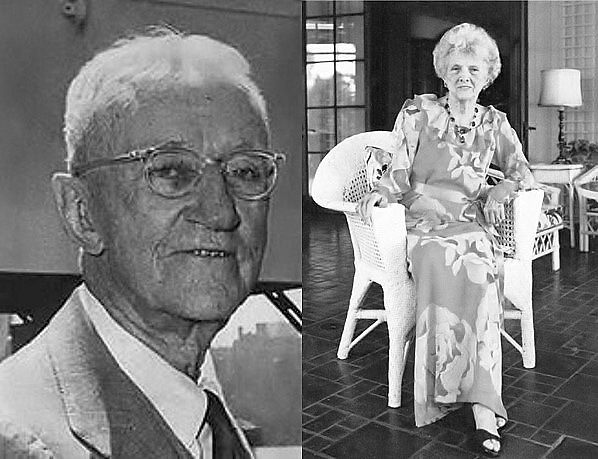

Meanwhile, Minneapolis society witnessed the marriage of John Sargent Pillsbury and Eleanor Lawler in 1911. John Pillsbury shared the same name with his great uncle, Governor John Sargent Pillsbury, who served as Governor of Minnesota between 1876 and 1882. He was the son of Charles Alfred Pillsbury Sr, who co-founded the Pillsbury Flour Company with the senior John S. Pillsbury in 1872. The junior John Pillsbury served on the company’s board of directors after his father and great uncle passed away and eventually became its chairman.

The Pillsburys soon began thinking about building a summer home on Lake Minnetonka. At that time, most of Lake Minnetonka’s wealthy residents lived in the city during the winter and moved out to the lake for the summer. In 1916, the Pillsburys purchased the Dunwoody property on Bracketts Point and tore down their Colonial Revival summer cottage. (The Dunwoody farm simultaneously became the site of Woodhill Country Club.)

The Pillsburys had commissioned New York architect Harrie T. Lindeberg, who specialized in country estates, to design their new Lake Minnetonka summer home. He rarely worked outside the East Coast, where he was especially popular among prominent American families such as the Morgans and Vanderbilts. The country estate that Lindeberg would design for the Pillsburys would certainly be a far cry from George Brackett’s 1858 campsite, as it would be a testament to all things civilized.

According to architectural historian Larry Millett, Lindeberg was known for thoughtful floorplans and exquisite craftsmanship. “A home can be elegant without being ostentatious,” Lindeberg famously remarked. “Simple traditional design, richly textured through the use of beautiful materials, expert craftsmanship and exquisite proportioning [can] rival the most magnificent palace while expressing the qualities of security and contentment appropriate to a home.”

Lindeberg’s design for the new home incorporated a mix of several styles. The lakeside façade could best be described as Georgian Revival, while the driveway façade featured elements of Jacobethan-Tudor Revival. Bricks for the exterior would be reused from other demolished structures to give the home an aged appearance. The interior of the home would feature many elements of the Arts and Crafts movement, including hand-carved woodwork and ironwork by famed Philadelphia blacksmith Samuel Yellin.

Millett further asserts that part of Lindeberg’s signature was to create outdoor vistas, relate the house to its natural surroundings, and create transitional areas where the architecture and the landscape would merge. Thus, the gardens, landscape, and the lake itself were integral to the house because they were rarely out of sight or mind. This mode of architectural planning is known today as “the Picturesque.”

Lindeberg completed his plans for the new Pillsbury house in 1917, with construction starting that summer. However, due to World War I, the home was not ready for occupancy until May of 1919. It was then that the Pillsbury family moved into the home and named it Southways. The name was purportedly conceived by Eleanor, as guests would have to travel “south a ways” from County Road 15 to reach the home. Construction was 100% complete by 1920.

Lindeberg and Eleanor didn’t agree on some aspects of the house. The completed home had ten bedrooms, including three sleeping porches for the six Pillsbury children that Lindeberg had objected to. Another issue was the color for the living room – Lindeberg wanted the room finished in butternut wood, but Eleanor wanted it painted teal-green. So, teal-green it was.

Although Southways exceeded 32,000 square feet in size and required a full-time staff of six, the Pillsburys only lived in the home during the summer months. As John and Eleanor aged, they began spending winters at their home in Palm Beach, Florida. However, some of the children built their own homes adjacent to Southways upon adulthood and lived on Bracketts Point in varying capacities for the remainder of their lives.

John Pillsbury retired from the Pillsbury Company’s board of directors in 1965. He passed away in 1968 at the age of 89. At this time Eleanor considered demolishing Southways, but ultimately decided to renovate the home instead. “When I became a widow in 1968,” she wrote, “I called Mr. Bolander, a contractor who is famous for wrecking buildings and houses. He came over and looked the situation over and said he never destroyed anything which could not be replaced, and that my house could not be replaced so, therefore, he would not destroy it. Consequently, I decided to make the house smaller.”

Only a few areas of Southways’s interior were modified during the 1968 renovations, mostly in the service wing. Eleanor lived in the house increasingly as the years went on. In the late 1970s she allowed scenes from the 1980 film Foolin’ Around to be filmed at the home. She enjoyed life at Southways until her death in 1991 at the age of 104.

Jim and Mary “Joann” Jundt purchased Southways in March 1992, only a few months after Eleanor’s passing. They soon contracted the restoration architectural firm of Beyer Blinder and Belle to rehabilitate the home and convert it for year-round use. The firm was particularly well-known for its participation in the restoration of Grand Central Terminal and Ellis Island buildings in New York. According to architectural historian Bette Hammel, the Jundts recognized Southways as a national treasure and planned to save as much of the structure’s fabric as they could.

With the assistance of local restoration architects MacDonald and Mack, all of the home’s service areas and mechanical systems were upgraded to contemporary standards. Many prominent areas of the home were restored to their historical appearance – Samuel Yellin’s granddaughter was even called upon to repair and create custom ironwork to match the original. One historical deviation was the color of the living room, which was stripped of its teal-green paint and refinished to expose the butternut wood as Harrie Lindeberg had originally intended. Work on the main house was completed in 1995, while work on the outbuildings continued until 1996. “This house belongs to the whole country,” Jim Jundt remarked when interviewed about the restoration process. “We’re just the caretakers.”

Ten years after the Jundts restored the home, they received a special visitor. President George W. Bush attended a fundraiser at Southways while on a visit to the Twin Cities in the summer of 2006. However, by this time the Jundts were spending more time at their house in Arizona, and in 2007 they put Southways up for sale. The original asking price of $53.5 million made Southways by far the most expensive residential real estate listing in Minnesota. The price was later reduced to $24 million.

After eleven years on the market and no sale, the thirteen-acre site on which Southways stood was subdivided into five separate lots in early 2018. The remaining 3.3-acre lot was relisted at $7.9 million. In June 2018, the caretaker’s house and its greenhouse were demolished. Then, in early August, news broke that a demolition permit had been filed for the main house.

The City of Orono approved the demolition permit on August 6. City administrators were purportedly reluctant, but ultimately had to approve the permit application because the house was not officially designated as a local historic landmark. The situation stirred a flurry of local press coverage and public outcry.

On August 22, it was announced that Twin Cities-based entrepreneur Tim George intended to purchase Southways and convert the home into a wedding and event venue. After contacting the city, George learned that the house had been sold to new owners and was about to be closed upon within the next several days. It was also learned that there had been at least one other matching offer on the property that had been turned down. Nevertheless, an agreement between George, the Jundts, and the new owners would have to be made before the closing in order to stop the demolition.

Such an agreement was never made, as the new owners closed on the house on Monday, August 27 and immediately demolished it on August 28. What had taken three years to build and another three years to restore was ultimately destroyed in a matter of a few hours on a rainy Tuesday afternoon. Various items were purportedly stripped from the home before demolition began and scattered about in the subsequent weeks. It is not yet clear what the new owners intend to build on the property, though another house is likely.

Aaron Person is a historian for the Museum of Lake Minnetonka and a board member of the Wayzata Historical Society. Joanie Holst is the President of the Wayzata Historical Society.

This is terrible! I remember when the Pillsbury family moved out and they had a sale. I was young and bought a wool tweed riding jacket that I still use.

My mother bought several Chinese bowls and some furniture.

This house was a treasure never to be replaced. The wood paneling along should have been kept. I will never understand why some people don’t appreciate the beauty which only increases with time! Very sad!